Dear Julia

(2020)

“I am out. Believe me this will be much better. Didn’t you get tired of being partially me and partially you for more than 60 years? My departure doesn’t mean you’ll be alone. From now on, you are one. One mind, one soul. At least, that’s my wish.”

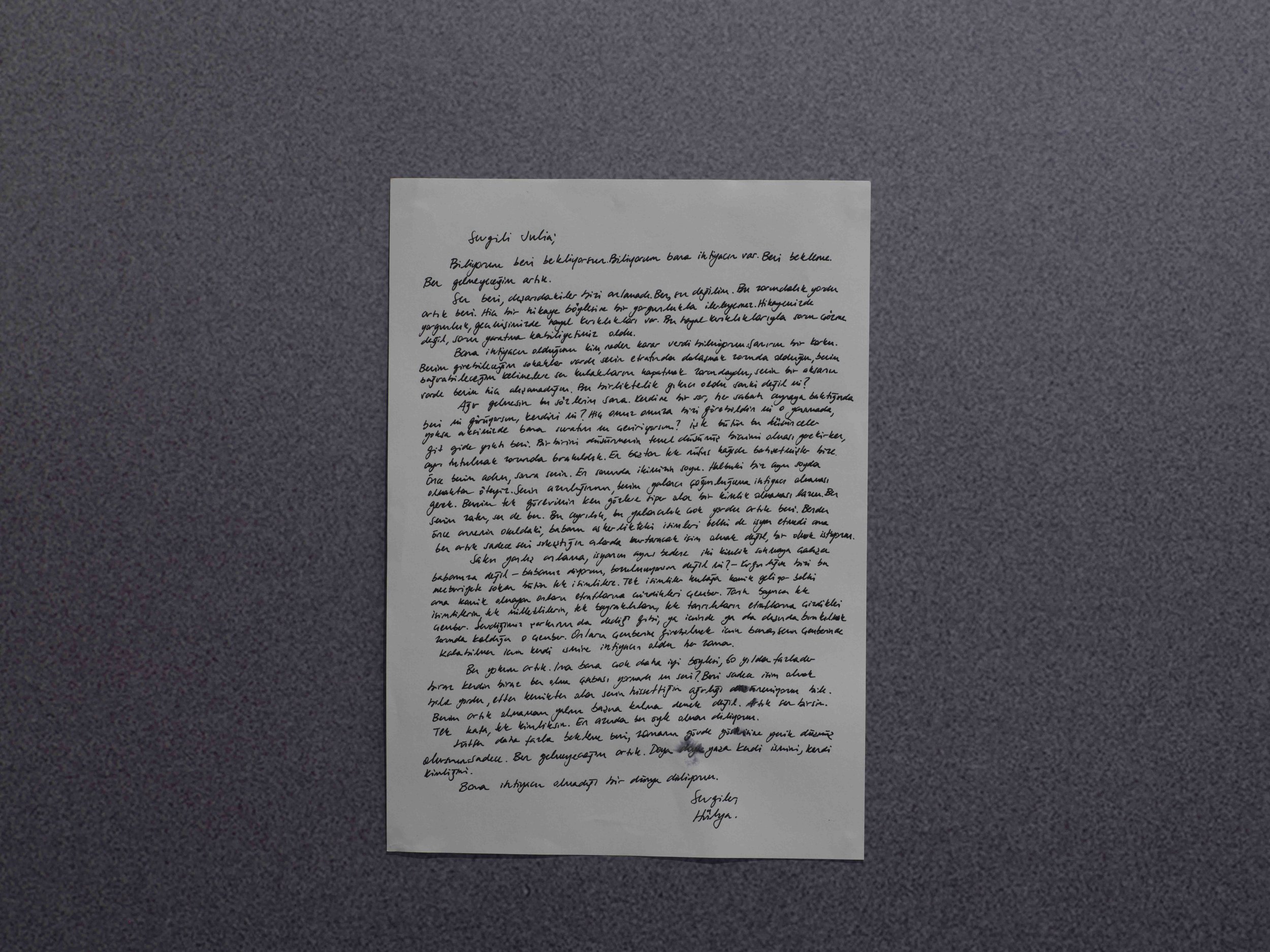

“Dear Julia” is a work inspired by a letter written from Hülya to Julia. Essentially, it is a breakup letter. It tells the story of two names, forced to bear each other for more than 60 years, finally reaching not reconciliation, perhaps, but some form of truce. It is a fictional letter. A letter from the Turkish name, confined to a single body, to its identity name.

Having two names is a common occurrence both among many minorities in Turkey and in Araz’s family. This second name is essentially a cover created to avoid discrimination. Just as this duality of identities exists in people, it also manifests in places across Turkey’s geography. One of these is İmroz and Gökçeada.

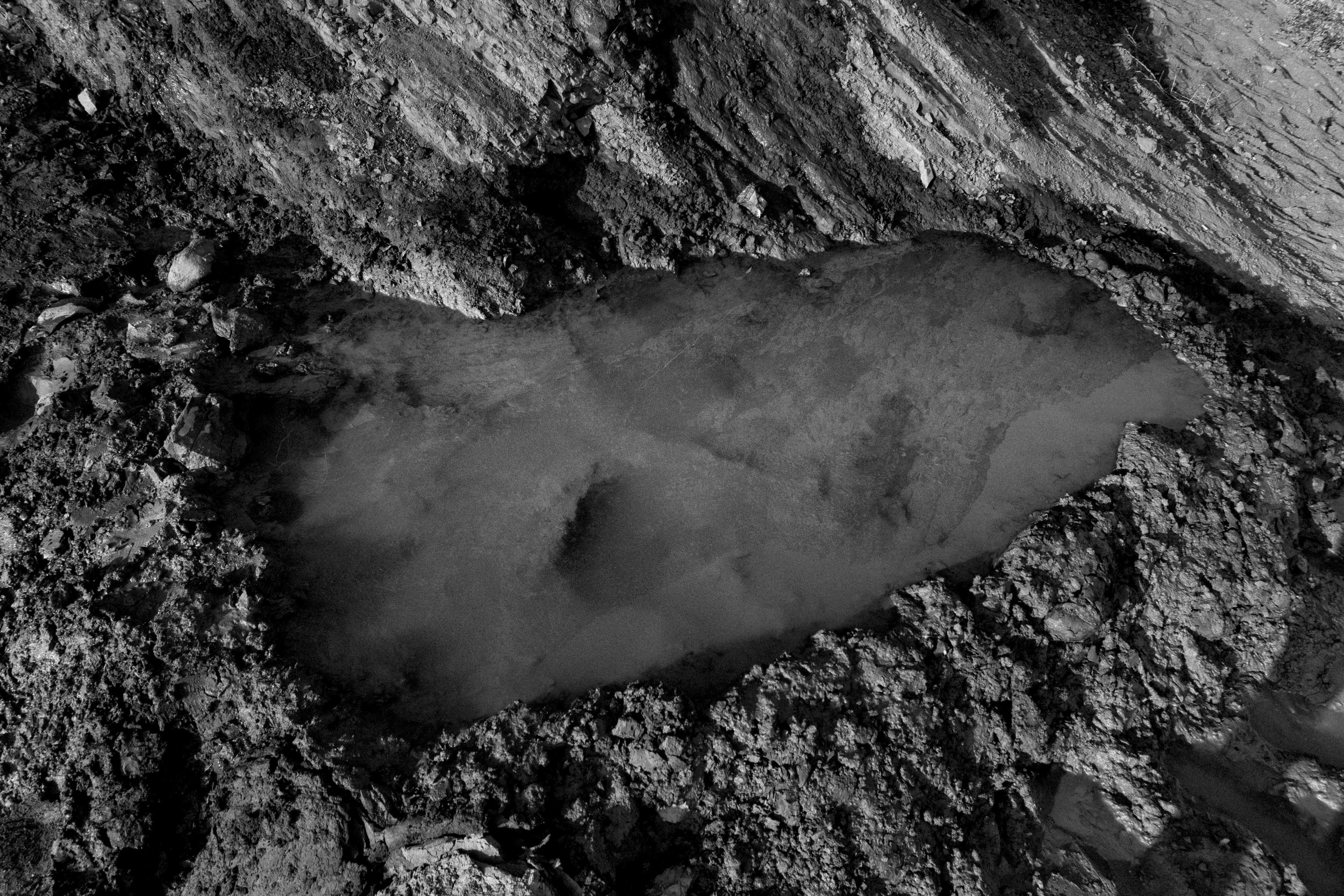

Known as a Greek island, İmroz has a tragic past filled with migration, death, and violence. Not subjected to the population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1922, the island was declared a military zone until the 1990s due to its geopolitical position. Following its military designation, fertile lands were seized, and the local population began to experience economic hardships. In the 1960s, an open prison was established on the island. Later, during the Cyprus War, whatever pogroms, expropriations, and assaults were happening on the mainland also occurred in İmroz. In 1965, a regulation was passed to Turkify the names of its neighborhoods and villages. In 1970, its name was officially changed to Gökçeada, erasing the former name from history, though not from memory. Throughout this process, the island lost 90% of its original population.

The installation of this work reflects this duality. On one wall, artist wanted to place a photograph of the island taken from the ferry amidst the fog—a representation. On the right side, Araz arranged small fragments that mimic the silhouette of the island and its essence. Because identity can never have a single representation; it is made up of the parts that form the whole. Among those photographs, the artist wanted to bring to life two women swaying. They were, in fact, the two sisters who invited Araz to this island. To her, Hülya and Julia are also two sisters, just as Gökçeada and İmroz are.